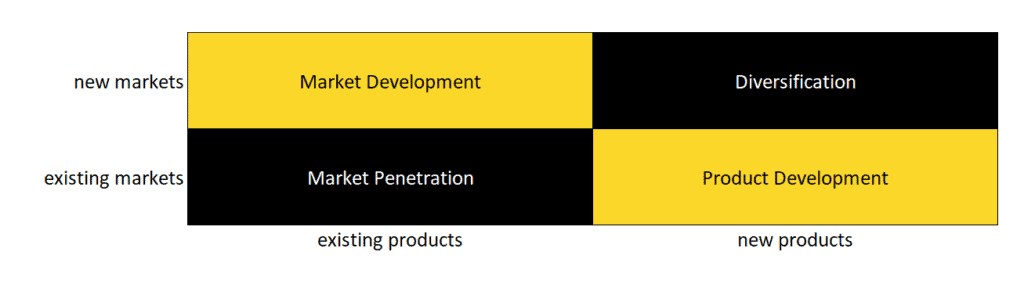

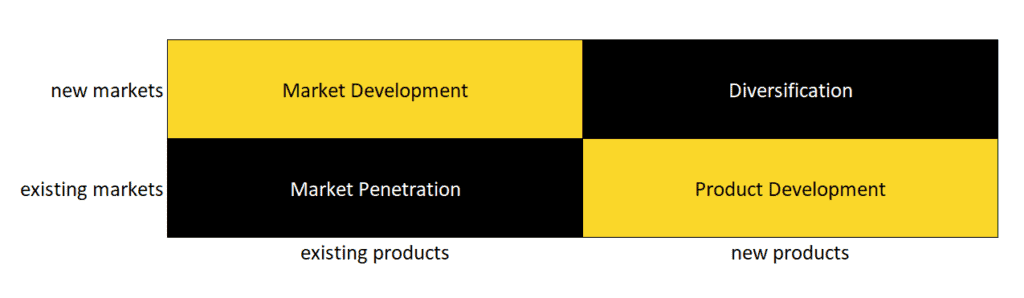

The ‘Ansoff Matrix’ is a tool used by marketers, CEOs, and other business leaders to provide a simple way to think about the opportunities and risks of all of their growth opportunities.

Essentially it allows you to ask the following question in a structured way:

How can we describe and categorise our potential growth strategies, to decide which we want to take?

The Ansoff Matrix breaks this down into two areas: products, and markets.

Due to this categorisation, the Ansoff Matrix is also known to many as ‘the product-market expansion grid’. It was first put in front of the world in a 1957 article in the Harvard Business Review, titled “Strategies for Diversification”.

Whereas there are many ways to categorise paths for growth, the Ansoff Matrix is useful in its simplicity: In a single tool, it allows you to describe all possible strategic directions within one single four-block model.

The Four Ansoff Cells

Let’s take a look at it in a little more detail, and how you may use it to decide on growth strategies.

- Market Penetration strategies are those which seek to take existing products, and sell more of them to an existing market.

- Market Development strategies are those which seek to take existing products, and bring them into new markets.

- Product Development strategies are those which seek to introduce new products into existing markets.

- Diversification strategies are those which seek to bring new products into new markets.

‘Market Penetration’ is seen as the least risky set of strategies. ‘Product Development’ and ‘Market Development’ each introduce risk, as they open the business up to product areas and market areas where they do not have experience. ‘Diversification’ strategies are seen as most risky, as they open up the organisation both to unknown product risk, and unknown market risk.

Each Strategy Area in Detail

Market Penetration Strategies (Existing Products in Existing Markets)

Where a business seeks to increase sales of existing products to existing markets, they’re pursuing a market penetration strategy.

When ecommerce companies expand advertising spend to try and acquire more customers for their existing product, they are attempting to increase their market penetration. Other ways to achieve this include pricing, loyalty activity, mergers/acquisitions of competitors within the existing market.

Market Development Strategies (Existing Products in New Markets)

Where a business seeks to sell existing products into new markets, it’s pursuing a market development strategy. That could mean expanding into new regions, or selling a B2C product to businesses, or packaging a product designed for one demographic to sell it to a new demographic.

A popular example of this is Coke Zero. Coke Zero is almost identical to Diet Coke, but the Coca Cola Company put millions into the development and marketing of this near-identical product in order to develop a new market for their sugar free alternative to coke. Whereas Diet Coke has always been marketed to, and largely purchased by women, Coke Zero is marketed to and largely purchased by men.

For ecommerce companies, internationalisation is often the first place to look when pursuing market development strategies: opening up a web presence to a new region may be as simple as negotiation with fulfilment partners, content translation, and ensuring adequate payment systems.

Product Development Strategies (New Products in Existing Markets)

Product development strategies seek to create growth by selling new products to existing markets. Uber offers well-known examples in this area: Originally a ride sharing app, they also sell bike rides and food delivery to their existing market in order to achieve growth.

For ecommerce companies, there are often easy prospects in this area. For example, a women’s dress retailer may expand into selling jewellery or outerwear. A watch company selling to teens and early 20s buyers via influencer marketing may develop a range of sunglasses to sell to the same audience, via the same channels. A store selling products purchased by a very broad audience – for example a book store – may diversify into selling other products via the same mechanisms (for example… Amazon!)

Diversification Strategies (New Products to New Markets)

Diversification strategies are usually deemed most risky: They entail selling new products to new markets. This is perceived as risky as the organisation may not have experience in either area, and therefore may have little existing competency in each.

Diversification is often split into sub-classifications. Those are usually as follows:

- Vertical Diversification is where a company expands their activity across the value chain. For example, a brand selling flowers online, but using a third party company to fulfill their orders, may begin insourcing that activity to gain greater control, and margin, which may be used to improve product, or buy growth.

- Horizontal Diversification (sometimes called ‘related diversification’) is where a company may enter a new market with a product that has some relationship to their existing product. An example of this may be a formal footwear company diversifying into athletic shoes: The company has competence around footwear, and is set up to store and ship footwear, and uses these advantages to enter a new market with a product somewhat similar to their existing.

- Conglomerate Diversification (sometimes called ‘unrelated diversification’) is where a company enters a market where they have no history, with a new product. Virgin Group offers several examples of this. From a music company, to a wine business, to a rail company, to an airline. Each trades under the same brand, each has a different ownership structure, and each is a different product serving a different market.

In Summary

In summary: The Ansoff Matrix is a useful tool for categorising your various growth options, and enabling you to weigh up risk in a structured manner.

Created by Igor Ansoff, a mathematician and business manager, it was first introduced in a Harvard Business Review paper in the late 1950s. Taught to business leaders and marketers all over the world, its principles also offer a simple structure to allow communication and a shared understanding of potential risks.

While it has limitations – for example not taking into account strength of competition – it provides structure needed to assist in planning, and generate new ideas for growth.